'Smart Window' Material May Make Better Batteries

Windows that darken to filter out sunlight in response to electric current, function much like batteries. Now, X-ray studies at SLAC provide a crystal-clear view into how this color-changing material behaves in a working battery – information that could benefit next-generation rechargeable batteries.

By Glenn Roberts Jr.

High-tech "smart windows," which darken to filter out sunlight in response to electric current, function much like batteries. Now, X-ray studies at SLAC provide a crystal-clear view into how the color-changing material in these windows behaves in a working battery – information that could benefit next-generation rechargeable batteries.

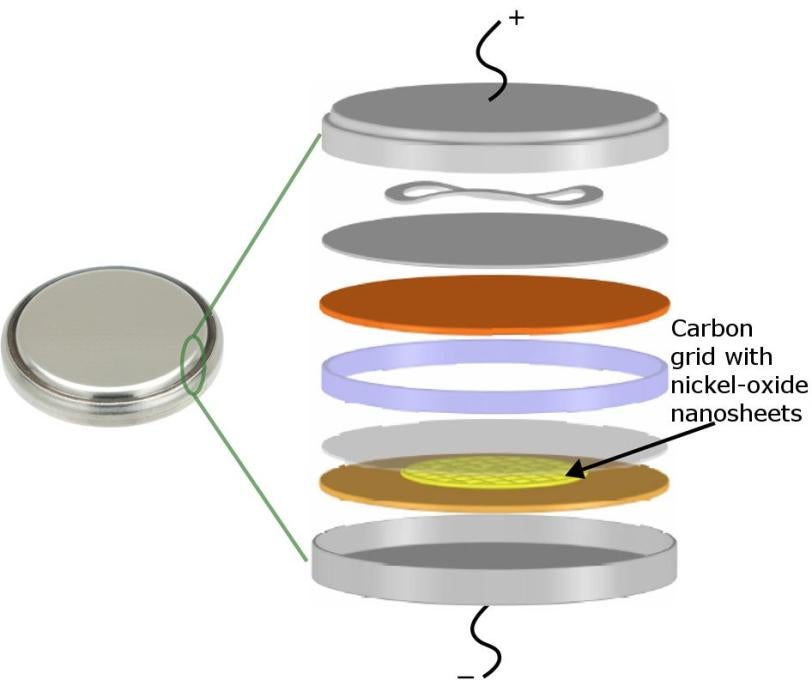

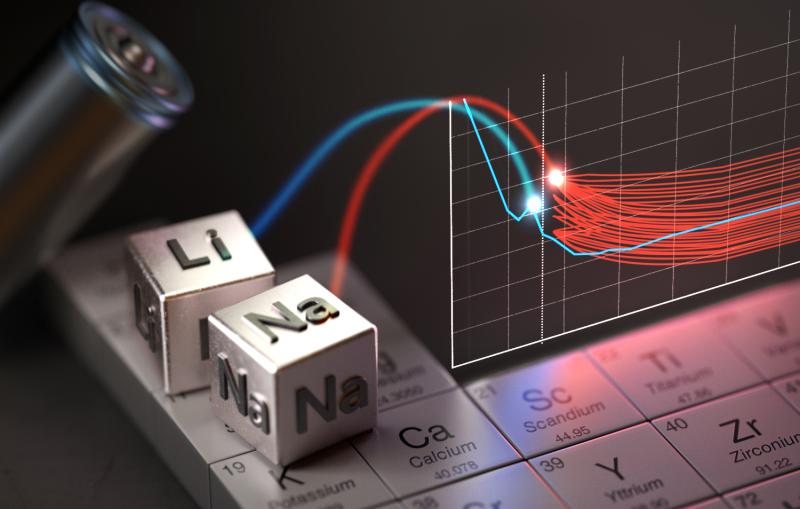

Researchers installed ultrathin sheets of smart-window material, nickel oxide, as the anode in a lithium-ion battery, and used SLAC's Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL) and equipment at other labs to study its changing chemistry and 3-D features.

"We switched our attention from changing the color of these materials to using them to store lithium ions, but the principle is the same," said Feng Lin of Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, lead author of the study, published in Nature Communications.

A Battery Anode at Work

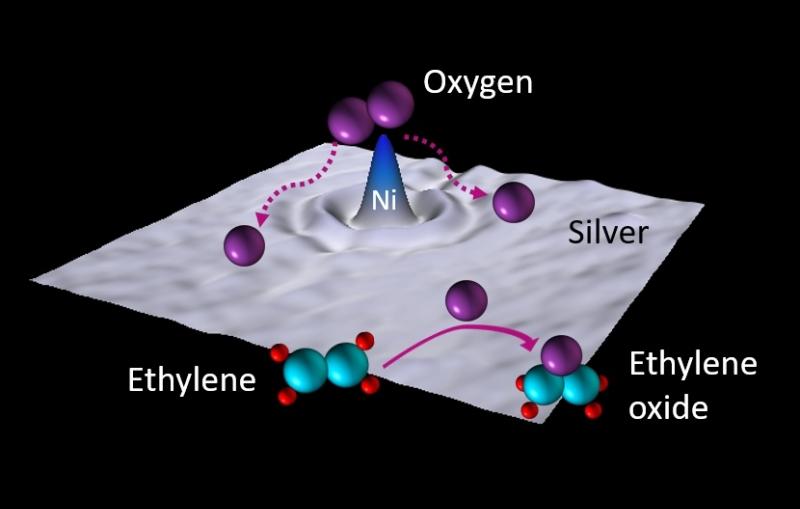

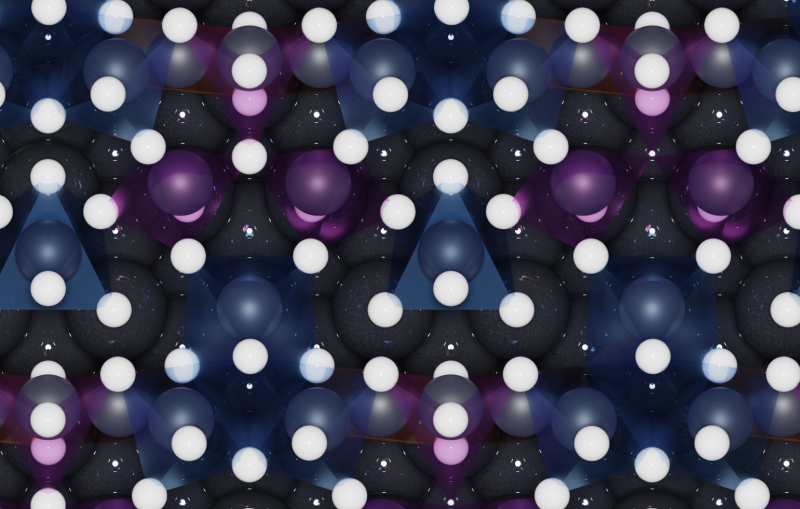

Smart windows have multiple layers of glass that sandwich ultrathin films or nanocrystal coatings of materials, such as nickel oxide. When a small electric field is applied, the charge moves through the glass to the ultrathin material, which serves as an electrode, and the window turns from clear to dark.

Earlier studies found that the interaction of these specialized thin materials with the surrounding glass cause structural changes that facilitate the flow of electrical charge through the glass – a property that is also beneficial for batteries.

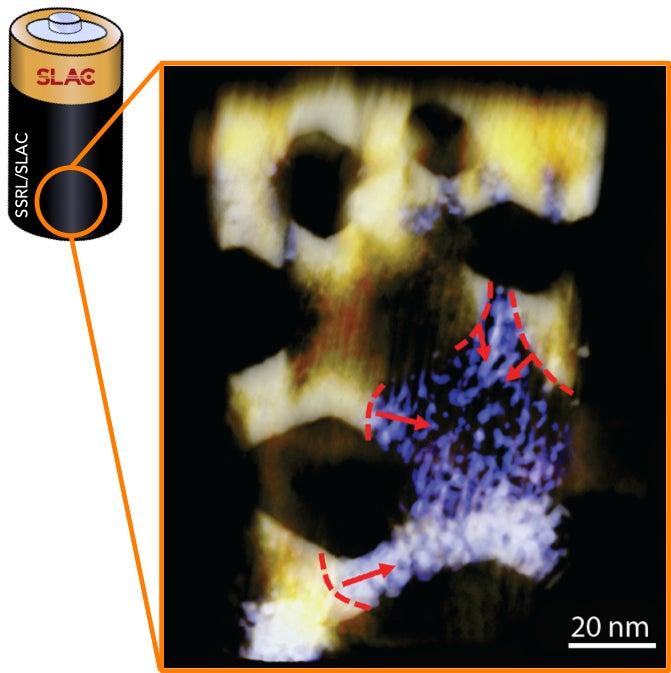

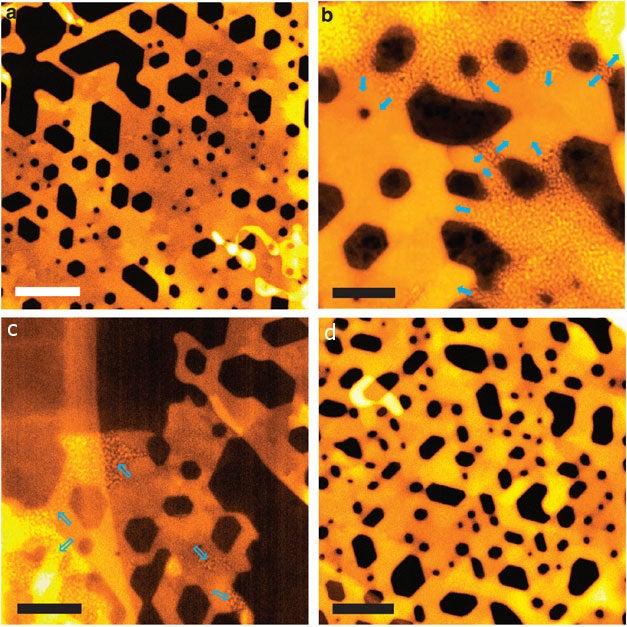

In this study, which uses nickel oxide as a battery electrode, researchers were able to see for first time exactly what happens when the battery's lithium ions make contact with the nickel-oxide layer and how the resulting reaction spreads out from several different points.

"It starts like a seed," said Tsu-Chien Weng, a SSRL staff scientist who collaborated in the research. "Then there are several different fronts for the reaction, and eventually a metallic framework is formed."

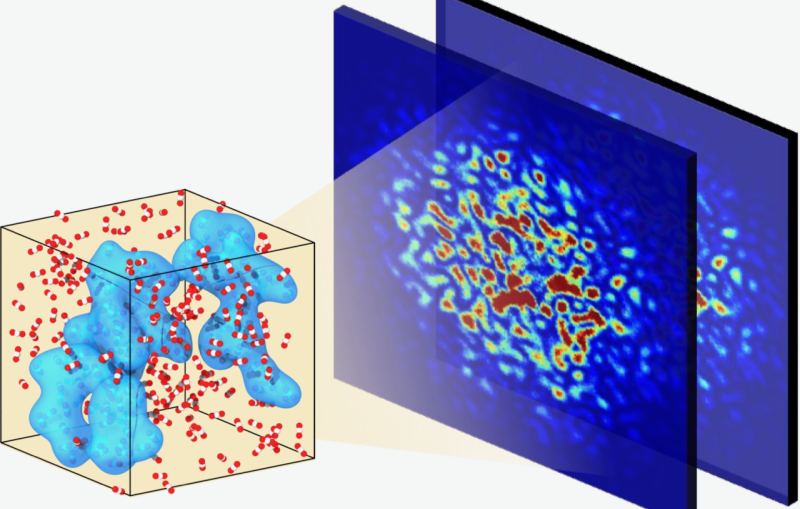

In addition, researchers observed how the surface of the nickel-oxide material "breathes" as the battery charges and discharges.

"We found this layer growing on the surface, building out," said Dennis Nordlund, a staff scientist at SSRL who participated in the research. "Then the layer goes away. It almost completely disappears. It's like a breathing layer. It is not necessarily specific to nickel oxide, and it has wide implications for battery materials."

This cyclical buildup of deposits from the electrolyte, usually referred to as the electrode-electrolyte interface, is an integral part of most battery materials but has been "a little bit of a mystery," Nordlund said, as it is generally challenging to study during a battery's operation.

In a typical lithium-ion battery, charged lithium ions migrate through a chemical solution – the electrolyte – into the anode when the battery is charging and into the opposite electrode, called the cathode, when the battery is discharging.

Because the breathing layer observed on the nickel oxide material builds up but then goes away, it could potentially limit the growth of “dendrites,” treelike fingers of lithium that are known to form on other types of battery materials and impair battery performance.

"If you can cycle and get rid of the layer so it does not build up over time that would be a huge step forward," Nordlund said.

Researchers used a technique known as X-ray absorption spectroscopy at SSRL to probe the nickel oxide material at depths of about 5 and 50 nanometers, or billionths of a meter, during the battery's operation.

"It turns out that these different probing depths are perfectly suited for studying the electronic structure at the surface of battery materials," Nordlund said, adding that these capabilities at SSRL open up a window for exploring many materials in active states. "We really feel uniquely positioned to address a lot of different problems in energy science using this same methodology."

The exploratory X-ray tools at SLAC and other collaborating labs have been key in understanding the properties of the nickel oxide material at the nanoscale, said Ryan Richards, a chemistry professor at the Colorado School of Mines who was involved in the study.

"We have submitted a number of proposals to look at different types of materials – how they form and what properties their surfaces have," Richards said. He said his ongoing collaboration with the SSRL staff is "really blossoming into a nice relationship."

The SSRL results were coupled with other findings from collaborators, including detailed 3-D images and movies produced at Brookhaven National Laboratory. Huolin Xin of Brookhaven Lab assembled the research team, which also included scientists from the National Renewable Energy Laboratory and Monash University in Australia.

Citation: F. Lin, D. Nordlund, et al., Nature Communications, 24 February 2014 (10.1038/ncomms4358)

Contact

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

SLAC is a multi-program laboratory exploring frontier questions in photon science, astrophysics, particle physics and accelerator research. Located in Menlo Park, California, SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science.

SLAC's Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource is a third-generation light source producing extremely bright X-rays for basic and applied science. A DOE national user facility, SSRL attracts and supports scientists from around the world who use its state-of-the-art capabilities to make discoveries that benefit society. For more information visit http://www-ssrl.slac.stanford.edu.

DOE's Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.